The concept of degrowth is now widely researched and practiced across Europe, but so far remained largely unexplored in the Netherlands. The first Utrecht Degrowth Symposium was organized to change this and to introduce degrowth thinking to the larger public. An interest in alternative, not growth-addicted pathways to sustainable future turned out to be high, as the event attracted more than 300 people from all over the Netherlands and from diverse sectors of the economy - academia, NGOs, public institutions, businesses. For those who could not come, we present below summaries of the three presentations. If you wish to watch the entire lecture yourself, video recordings can be found at the end of each summary.

Lecture 1/3: Degrowth as a project for societal transformation: its science and its relevance

Dr. Barbara Muraca, University of Oregon

The presentation started with debunking a common myth about degrowth:

“Degrowth is not a reversal of things that we had before. It is not an elephant put on a diet. It is a different creature”.

“Degrowth is not about reversing GDP. People think that degrowth is about shrinking, having less, living simpler. It’s not the point. The point is that we need a change in the structure of society, and it’s not just a desirable path for the environment. This is the necessary path for us not getting into trouble”.

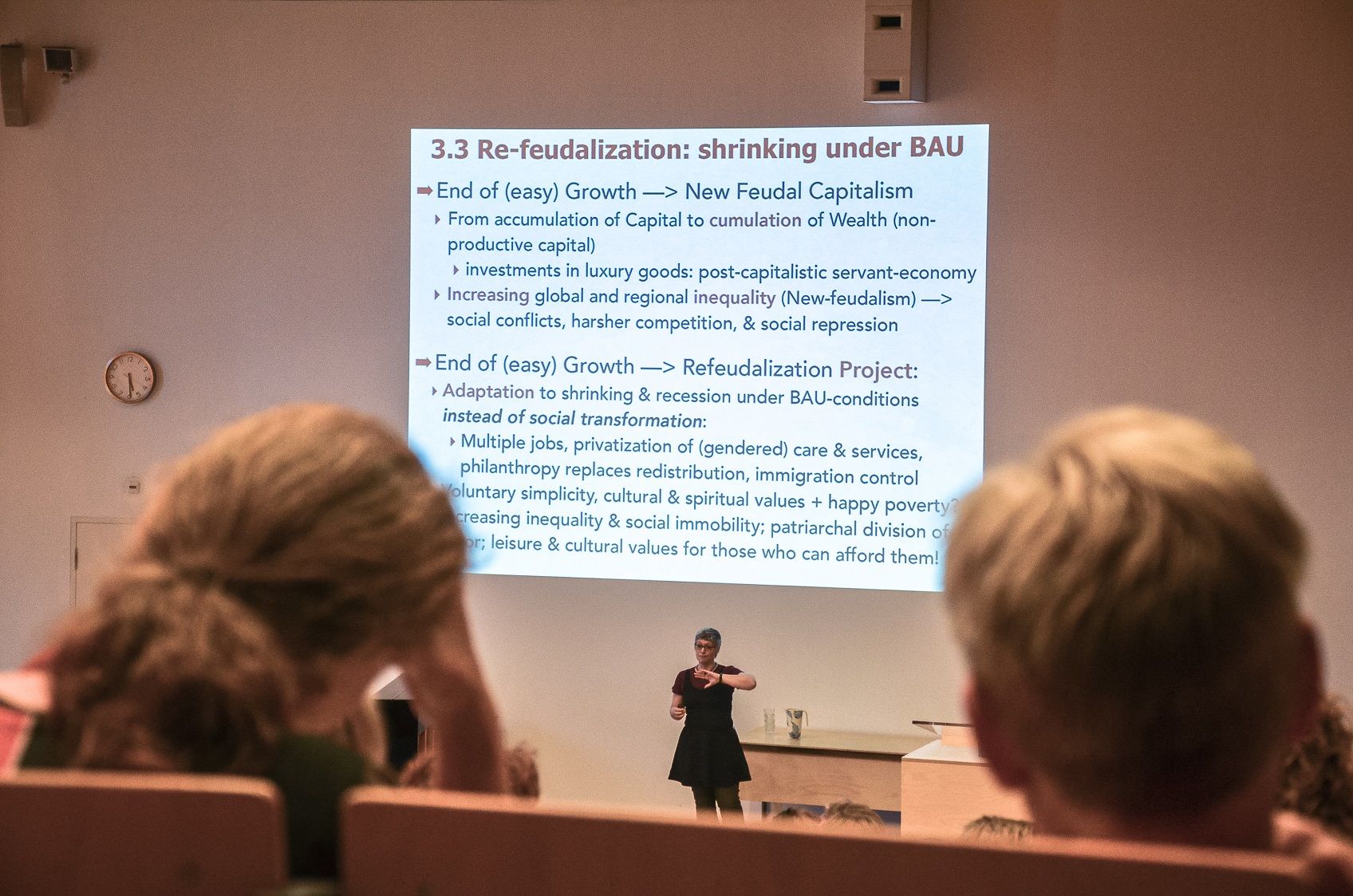

Barbara Muraca continued by explaining a larger context and presenting the main critique of the growth paradigm. First of all, it is commonly agreed that GDP is not the best measure of well-being because GDP does not distinguish between transactions that are bad for society and good for society - it just measures the throughput of material and financial resources in a given time frame. Secondly, the idea of dematerialization, decoupling growth from the use of material resources didn’t work well so far as the structure of economic growth is directly related and addicted to profit maximization and accumulation. The problem is aggravated by the fact that we currently use resources beyond regeneration capacity. Thirdly, growth has become a mental infrastructure, a measure of not just having more, but a measure of being better. We are all caught in this paradigm, and we are addicted to it. It is especially noticeable in the US, where people invest in themselves to constantly being more productive than others. Lastly, growth is a structure of modern capitalistic societies. Since the second World War, growth played an immense role in stabilizing societies. However, it turned into a ‘crazy bicycle’ that needs to keep accelerating in order not to fall down. This design of growth allowed not to think about redistribution, growth replaced it through the idea of ‘trickle down’. However, we reached the end of easy growth. The costs are getting higher and higher to sustain it – in terms of environmental pressures, stress, burnouts, etc.

There are different views on what comes after the conventional idea of ‘easy growth’. One of them is the neoliberal restructuring which, for example, includes the concept of the circular economy. However, the circular economy can’t work through the paradigm of growth simply because if the goal of the system is the accumulation of capital and profit maximization, it eats up what it gains. For instance, when waste management is made circular under the paradigm of growth, more waste is constantly needed as it generates profit. Furthermore, an important question is – where we draw boundaries of circular systems? Which vital processes we ignore or take for granted?

Another possibility after the end of ‘easy growth’ is re-feudalization which means that instead of accumulating capital for reinvestment, market players accumulate just for their own benefit. This leads to greater competition for resources and, consequently, to rising inequalities, harsher social repressions, border control, etc. The issue of redistribution is not addressed in this scenario.

However, there’re alternatives to the idea of growth itself – and degrowth is one of the umbrella concepts. It’s not about stopping moving, but changing the structure addicted to economic growth. The ‘bicycle of degrowth’ doesn’t have to constantly accelerate in order to keep moving. It can also hold other living and non-living entities. For this scenario, as Barbara puts it, we need the courage of imagination, we need to dare to imagine radical alternatives, we need to rethink how economic relations are structured, how time and space are defined, how, by and for whom knowledge is produced. It’s also a matter of changing practices and experiencing how alternatives feel like.

Many communities are already experimenting with degrowth ideas and practices, in the Global South more than in the Global North. An important question is – how can we build alliances, solidarity to support each other on the path to a new organization of society?

Below you can find the recording of the lecture of Barbara Muraca, the slides are visible in the video but can also be viewed separately here on slideshare.

Lecture 2/3: Degrowth in the global South?

Dr Julien-François Gerber, International Institute of Social Studies

The presentation discussed the applicability of the concept of degrowth to the global South. It opened with the following questions: doesn’t “development” require growth? Aren’t the rich only supposed to de-grow? Wouldn’t “degrowth in the global South” be another form of colonialism? The first question was explored by confronting different views. For mainstream economics, development certainly requires growth, and three ideas are often mobilized to justify this link, although all three are problematic. First, it is said that the benefits of growth will trickle-down to the poorest. However, assuming constant high growth rates, we would have to wait more than 200 years to get everyone at a daily income of $5 and we would need to grow the global economy 175 times! Second, the various Kuznets curve narratives arguing that very rich countries are able to deal with their social and environmental problems do not provide a convincing justification for growth. Finally, the “green growth” hypothesis based on a decoupling of growth and resource use is equally unobservable in the real world.

For a growing number of heterodox economists, in contrast, the idea of degrowth in industrialized countries is starting to be accepted. However, degrowth is seen by most of them as not applicable to the global South. Some heterodox economists have championed a Green New Deal, namely a massive “green growth” transition to renewable energy, but unfortunately without problematizing levels of consumption. This is problematic because such massive green investments are likely to be biophysically impossible if one wants everyone to consume like a Westerner. In any case, degrowth is not about shrinking “everything” and imposing austerity everywhere; degrowth is about resizing/downsizing our use of resources, while reorganizing society radically differently, with more equity, conviviality and democracy. Put this way, it is hard to see why this would only apply to the global North.

Moreover, it would be naïve to assume that degrowth ideas have only come from the global North. After a quick review of major South Asian thinkers, it quickly turns out that similar ideas have been discussed there at least since the 1910s. Sure, the global North should degrow to stop its unsustainable metabolism and to decolonize the world system. But the critique of the growth tyranny certainly also applies to the global South, as many global South scholars have pointed out.

The presentation continued with four examples of countries in the global South that are of relevance to the degrowth project. Cuba, Vietnam and Costa Rica manage to have high levels of life expectancy, wellbeing and equality, and low ecological impacts while keeping their GDP low. Bhutan, for its part, developed interesting policies limiting growth, including its famous Gross National Happiness index. Degrowth has a lot to learn from the global South.

The presentation continued with five degrowth-oriented policy actions applicable to the global South. First, it was argued that like Cuba or Bhutan, policies should focus on needs fulfilled instead of GDP growth per se. To boost undifferentiated growth is not the best way to overcome “true” deprivation. Such an approach would require more collective planning for “true” needs and less market only for those who can afford it. Second, it was said that the external debt should be canceled while the ecological debt should be acknowledged. Third, it was argued that fulfilling needs does not necessarily require a general increase in wealth, but a better distribution thereof, within and between countries. Fourth, extractivism should be stopped: there have been calls for “post-extractivism”, seen as a necessary move away from economies dependent on (Northern) extractive industries. Finally, it was argued that we need to collectively reflect on the “good life”, on what is important in our communities and on what we need for achieving it. Many cosmologies in the global South – like Buen vivir in the Andes or Tri hita karana in Bali – articulate what constitutes a “good life” and do not focus on a constant increase of production and consumption.

As a way of concluding, the presentation went back to the three opening questions. To the question of whether only the rich should degrowth, it was said that degrowth should not be understood as a “punishment”, but as a radical project of social and ecological healing seeking equality and sustainability. As such, degrowth cannot only be relevant to the rich!

Below you can find the recording of the lecture of Julien-François Gerber, the slides are visible in the video but can also be viewed separately here on slideshare.

Lecture 3/3: Degrowth in practice: examples from Germany

Nina Treu, Konzeptwerk Neue Ökonomie

The presentation started with an opening disclaimer on other ways of doing degrowth – “don’t necessarily look to Germany!” The first example was the successful Degrowth Conference of 2014 in Leipzig. More than 3000 people attended it and it veritably launched degrowth ideas in the country. The organization was very participatory and horizontal, characterized by consensus-based decision-making. The organizing committee was composed of activists and academics. It was overall a nice example of performative politics, as in the successful socialization of cooking which only used local, vegetarian and organic products. Two related conferences in 2011 and 2021 actually prepared the ground for the Leipzig conference.

The presentation continued with specific examples where degrowth was linked to social movements. There are many degrowth-oriented projects that look like “anarchism” (“local”, “horizontal” and “alternative”), but it is more difficult to convince workers unions. Union leaders are generally on board for “post-growth”, but not “degrowth”. The word degrowth remains problematic. Nina suggested finding a local word for degrowth, because there is a risk that it would otherwise remain academic. Unlike Barbara Muraca who emphasized that the word “degrowth” hits at the heart of globalized capitalist modernity, Nina argued that we need both universal and particular concepts.

In Germany, degrowth linked very well with climate justice. The concept was “naturally” added to the analytical framework of climate justice activists. The movement Ende Gelände (“Here and no further”) is a large civil disobedience movement seeking to limit global warming through the phasing-out of fossil fuels. Every year since 2015, up to 4000 activists have carried out direct actions to stop open-pit coal mines and coal-fired power stations. In parallel, an annual degrowth summer school has been organized, explicitly linking “degrowth in action” and climate justice. The summer schools are prepared by Konzeptwerk Neue Ökonomie, the activist-academic NGO of which Nina is a member.

The presentation continued with the links between degrowth and migration (antiracism). Nina started by observing that degrowth is still very white and middle class. She noted the difficulty, in Germany, to connect ecological and antiracist movements. An attempt was made and a conference gathering 700 participants was organized. At the end, however, the results weren’t too conclusive.

Degrowth was also tentatively connected to care and feminism. Nina emphasized that we have to make the invisible work done to reproduce/care for people visible and that this should also be central in degrowth. A lot of work still remains to be done, she said, on linking the “care revolution” and degrowth. More generally, German degrowth activists have tried to form coalitions with other social movements, like Attac etc. While doing this, degrowth was challenged by social movements, but it was useful and constructive. Perhaps we need a meta-term that would be a common denominator to more movements.

A Global Degrowth Day was also launched in Germany and spread across other countries like the Netherlands. In parallel, an online platform – degrowth.info – was created to support degrowth ideas way beyond academia. In the future, a fundamental reflection will need to take place: who should be brought together? What are the hot topics/windows of opportunity? Possibilities include education and school strikes, fossil-free movements, and migrants food issues.

As a conclusion, Nina offered two important recommendations. Firstly, do not rush, otherwise, the project becomes undemocratic. Instead, take care to work democratically throughout, slowly and carefully, inspired by anarchist tactics. Secondly, work not to change policy or individual gardens, but through communities, inspired by feminist strategies.

Below you can find the recording of the lecture of Nina Treu, the slides are visible in the video but can also be viewed separately here on slideshare.

Panel debate – Prospects for degrowth

Nina Treu, Ties Temmink (Extinction Rebellion NL), Kris de Decker (Low-Tech Magazine), moderated by Ana Poças ( PhD at UU and member of Ontgroei)

The debate started with pitches from Ties and Kris. Kris showed the audience his website – Low Tech Magazine, which has the tagline that “Not every problem needs a high-tech solution”. In the website there is a collection of inspirations of low-tech ways of doing things, many drawn from the past, and also from around the world. Kris acknowledged the possible contradiction in advocating for low-tech on a web platform. He also told about how he and his team developed a Solar-powered version of the website, and redesigned it to use the much less energy than the average website. The solar-powered website depends on the sunlight in Barcelona (where he lives) plus a small energy storage. The battery level is clearly visible on the website and the site is only online when there is enough solar energy stored, a entirely different way of dealing with limits of sustainable energy availability.

Ties’s pitch was a strong call for action. He sees degrowth as the future to strive for, the alternative to barbarism. He explained the arguments of Extinction Rebellion, alerting to the very short timeframe we have to prevent the worst consequences of climate change. He provoked the audience to take an active part in this struggle, especially academia which spends much of its time writing papers and talking within its bubble, but should take steps to go beyond this bubble and rethink its role in society in a time of climate emergency. Ultimately, Ties, addressed everyone in the audience - "What do you want to be able to tell your children in the future, when they ask you what you did in these times of climate emergency?"

Picking up the call for action by Ties, and from other members of the audience, Ana started the debate with the question: do we still have time to have these discussions, given the climate emergency?.

See here Ana’s reflection on the answers from the speakers and audience.

-----

In the 1st Utrecht Degrowth Symposium we also had live music played by Marte Gerritsma, and we exhibited cartoons about degrowth, modern life and alternative futures created by Lara, the escape artist.

Impressions from the Symposium can be found on Ontgroei Twitter page. A photo album from the event is uploaded to Facebook.